- Home

- Gwen Russell

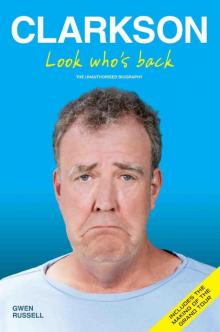

Clarkson--Look Who's Back

Clarkson--Look Who's Back Read online

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

1: A MOTORMOUTH IS BORN

2: THE RISE OF A LAD

3: MARRIAGE & MOTORS

4: STRAIGHT TALKING

5: KING OF THE ROAD

6: LIFE IN THE FAST LANE

7: A SUDDEN CHANGE OF GEAR

8: A REGULAR GUY

9: BACK TO THE FUTURE

10: CLARKSON STRIDES OUT

11: WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE?

12: ‘AWARDS NIGHTS ARE JUST A LOAD OF BLONDE GIRLS WITH THEIR BOOB JOBS OUT’

13: CLARKSON STRIKES OUT

14: AROUND THE WORLD WITH CLARKSON

15: CLARKSON RETAKES THE FALKLANDS

16: BUST UP

17: TOP GEAR ON STEROIDS

PLATES

COPYRIGHT

CHAPTER 1

A MOTORMOUTH IS BORN

Jeremy Clarkson is a modern phenomenon. There is no missing him wherever he goes: 6ft 5in tall, in his trademark jeans and mop of unruly hair, these days Clarkson is one of the most recognisable men in the country. And, in this era of vacuous celebrity, he is in many ways a breath of fresh air. Famously acerbic, refusing to bow to authority and not overly concerned about who he might upset, Jeremy has metamorphosed beyond his initial persona as the country’s best known motoring broadcaster into a national celebrity who has written books, hosted his own chat show and turned his hand to any number of different crafts. And he’s lasted the course, too. It is almost thirty years since Clarkson first appeared on BBC’s Top Gear, and his popularity is as high as it ever was. There’s no chance, for the moment at least, that he’s going to go away.

Jeremy has certainly carved out a niche for himself in modern Britain. Love him or loathe him – and Clarkson is one of those men who divides public opinion – you have to admit that he’s made himself known nationwide for his acerbic views, his blunt style of broadcasting, his occasional outrageousness and his sound ability to tell it like it is. He’s a bloke’s bloke, a man’s man and, whatever your views about him, he’s simply someone who can’t be ignored. But how, exactly, did he get to where he is today?

Clarkson’s background is a surprise. He likes to come across as a bit of rough, but the truth is that his was a privileged childhood, with a stable family, good schooling and an exceptionally enterprising mother. On 11 April 1960, Jeremy Charles Robert Clarkson was born to Shirley, a teacher, and Edward, a travelling salesman. It was a comfortable household, although not a rich one, with both parents doing well and able to provide for Jeremy and, a couple of years on, his younger sister Joanna.

The Clarksons were not an inward-looking family. They dealt with everything by having a laugh and that is something that has clearly built Jeremy into the man he is today. His home life was robust, with lots of teasing and with no one taking anything too seriously. It was an utterly secure environment in which to live, with the parents dedicated to the improvement of both themselves and their children. And they were in deadly earnest about that. They might not have been prone to taking life too seriously, but to them their children’s education was of paramount importance and, from the very start, they were determined it would be as good an education as it was possible to get and they would work as hard as they needed to in order to attain it.

‘From early on, I realised they wanted a private education for my younger sister Jo and I, but they couldn’t afford it, so Mum started making bits and bobs on the side,’ Clarkson recalled. ‘Pouffes and cushions to sell to the neighbours. She was, and still is, a wonderful seamstress.’ She was about to put these talents to even greater use.

This was middle-class England on the cusp of the sixties: conservative and non-threatening. The family had a good life and their material comfort, which was not excessive but more than enough for a decent lifestyle, was not the only element of Clarkson’s background that shaped him: so, too, was the fact that it was so very secure. Whether or not you agree with his assaults on public consciousness, it actually takes some guts to stand up and take on pretty much everyone. And the only reason Jeremy is able to do so is because he is secure in himself. The knowledge that he was at the centre of his parents’ lives gave him the confidence to become such a strong personality.

But the family was soon to become rather more prosperous, all because of a happy opportunity that was shortly to arise. No one had foreseen it when his mother went into business, but it was to have a lasting effect on Jeremy’s life. Shirley, who went on to become a magistrate, was an exceptionally able woman: much taken with Paddington, of the Paddington Bear stories, she decided to make little Paddington figures as a Christmas present for Jeremy and his sister Joanna out of fabric purchased from the local market in Burghwallis, near Doncaster, where the family lived.

Unfortunately, she couldn’t make the little bear stand up, and so hit upon the idea of putting him in Wellington boots – and so the world-famous Paddington figure was born. For the toys were so popular with her children that Shirley decided to set up a business to make and sell the bears; it was a decision that brought the family some real degree of prosperity and allowed the Clarksons to send Jeremy to a good public school. ‘I still remember the day Mum and Dad told us they were jacking in their jobs to set up a toy business,’ Jeremy recalled. ‘Marine Boy was on the telly and I thought, “Do what the hell you want, Mother, but please shut up!”’

Using her middle name as the name of the company, in 1968 Shirley set up Gabrielle Designs. It was an immediate success. The company grew quickly and, by 1976, demand for the Gabrielle Paddington was so great that production had to move from Shirley’s kitchen table to a factory in Adwick Le Street, which became known as the ‘Bear Garden’. It was Paddington Bear who funded Clarkson’s schooling, holidays and agreeable childhood, and it was Paddington Bear who even gave him some gainful employment, when he worked for the family business for a short time after leaving school.

Edward also began to work for the company, dealing with sales and marketing, while Shirley concentrated on production. So taken was Michael Bond, Paddington’s creator, with the little figures that he described them as ‘the definitive Paddington’. But that was not the end of Shirley’s endeavours: in 1992, by which time her son was already famous, she was granted the licence to manufacture the Classic Winnie the Pooh by The Walt Disney Company. Three years later she sold the company on; three years after that, it shut down.

However, Shirley was not the first member of the family to have displayed an entrepreneurial streak. Jeremy came from a long line of people who were prepared to take any chances offered to them: his mother might have been a very successful businesswoman, but she was only following a family tradition. Many years later, when taking part in a BBC programme about tracing family roots called Who Do You Think You Are?, Jeremy discovered that one of his ancestors had manufactured the screw-topped Kilner jar, which was sealed with a rubber ring to preserve food and exported all over the world in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

For some years the Gabrielle Paddington was the most popular toy in Britain and it is safe to say that the Kilner jar must, decades earlier, have been one of the most popular pieces of kitchenware in the world. Indeed, its creation was part of the whole process by which food could be properly stored and, in the years to come, revolutionise cooking.

Returning to the 1960s, however, all this was both past and in the future. Jeremy’s early childhood was a happy one: the family lived in a 400-year-old farmhouse although, by the time he was fourteen and already 6ft tall, Jeremy’s head was hitting the ceiling. It was his father who was the family cook, something that might explain the fact that, in later years, Jeremy himself was rather proud of the fact that he too could follow a recipe an

d, notably, male chefs have never come in for the sort of lambasting he dishes out elsewhere.

‘Father cooked, he was a superb cook, was and still is the best cook I ever encountered,’ said Jeremy in the 1990s. ‘School friends would want to come over and eat and Father was unhappy unless I brought home twenty of them. He spent two days cooking cakes for the birds.’ As for his mother: ‘Mother rustled up puddings; Mother ate out of a tin.’ The fact that Jeremy himself became an extremely competent cook as an adult is one of the many sides to him that the public might be surprised to take on board.

But it is his mother who Jeremy most closely resembles, certainly in temperament. She was as jolly and as straightforward as her son was to become, refusing to take life seriously and never letting anything get her down. ‘I was always a bit of a mother’s boy,’ Clarkson once said. ‘I can certainly see a lot of me in her – she’s one of those life and soul of the party, bang the furniture, make a joke about anything characters. Even when I was an idiot teenager, I was in awe of her and how she could hold the entire room with one of her stories. Her friends used to call them “Clarkson stories” – they were these elaborately exaggerated anecdotes. I’m sure her friends thought she made them up.’

As for his northern heritage, Clarkson could become a bit irritable about suggestions that his upbringing was some kind of cliché. ‘No, we did not have marmalade sandwiches, not at home, but I was partial to halibut and peas, and raspberries and cream – we had a large garden given over to raspberries.’ In fact, he tended to associate halibut – with parsley sauce – with his grandfather, who was a doctor and author, and who played a large part in the young Jeremy’s life.

He would take the young boy out and about with him and, in later years, would also help his grandson to find gainful employment. Jeremy adored him, although he would never have put it in exactly those words: his was the more gruff type of appreciation that some men find easier to express. ‘Built a house by a railway line and everyone said he was mad and then he bought the spur line,’ Jeremy mused of his grandfather. It was his way of saying what a wonderful man his grandfather was.

The family would holiday in Padstow in Devon where, of course, Clarkson père was in charge of the cooking, and occasionally in France. The young Jeremy was becoming something of a bon viveur: he once recalled eating langoustines for the first time on one of these holidays and it was something that ‘started a love affair with shellfish that persists to this day’. His grandfather would also take him out to smart restaurants, such as the Gingham Kitchen in Doncaster and the 1492 in Marlow. ‘[It] was very expensive and I ordered strawberries and cream,’ Clarkson recalled. ‘I was into lobster thermidor. [We] went to the Newton Park Hotel, which smelled of Brussels sprouts cooked for some time. When you reserved a table they asked, “What vegetables?” so that they could start cooking.’

And, even as a child, Jeremy was beginning to stand out. He had a combative streak and was always determined to take on allcomers. As an adult he might not care at all what other people think, but as a child he was still keen to impress, although his way of doing this was by being a rebel. His mother once recalled that, when he was very young, she’d come to the conclusion that as an adult he’d either have no friends or hundreds – and, despite all the feuds he has become embroiled in throughout his adult life, it’s fairly safe to say that the latter has turned out to be the case.

Jeremy was, however, not an easy child to bring up. Fairly early on, he lost interest in academic studies, something that caused his long-suffering parents no end of concern. ‘I’m sure Jeremy thinks he was a normal child, but my God he was a handful,’ Shirley recalled. ‘Do you know something? He gave up work when he was eleven. He went from being top of the class to bottom overnight. He told us he didn’t think physics or maths were going to be any use to him because he was either going to be Alan Whicker, an astronaut or king – in that order!’

By the time he reached an age to go to senior school, Jeremy’s parents were able to send him to Repton School, again, not a place entirely in keeping with his rough-and-ready image. The school had a history of turning out students who would go on to make their mark: old boys include author Roald Dahl, sportsman CB Fry and broadcaster and comedian Graeme Garden. Indeed, given both its academic reputation and its stalwart image, Repton is a somewhat surprising place for Jeremy to have been educated, even though he did turn out to be one of the school’s self-confessed rebels.

The history of the school is in some ways a microcosm of the national history of the period and is worth relating, very briefly, here. In 1557, Sir John Port of Etwall died, leaving no male heir and, in consequence, left behind a sum to found a ‘Grammar School in Etwalle or Reptone’. There, scholars were to pray on a daily basis for the souls of his parents and for other members of the family.

Two years later, the executors of the will bought, for the princely sum of £13.10s, some land that had once been the site of a twelfth-century Augustinian Priory, and some buildings that had escaped destruction during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. These were the Guest Chamber and Prior’s Lodging, Overton’s Tower, the Tithe Barn and the Arch, all of which are now part of the school.

In the nineteenth century, the school came into its own. Steuart Adolphus Pears became headmaster in 1854, a post he held for two decades, and it was under his guidance that the school really became one of the great public schools of its day, a position it still holds. Its reputation had declined since it had been founded and Pears found just forty-eight pupils in situ: within three years that number had doubled, staff numbers were increasing and the purchase of land had begun that would make the school a force to be reckoned with.

As in its earliest days, Repton’s history in the nineteenth century reflected the wider changes going on in the Victorian world. The industrial revolution brought both progress and wealth in its tracks and the school, like so many of the age, benefited from this. It began to invest in more land, which gave rise to the building of the School Chapel, Orchard House, Latham House, the Mitre and Brook House. Nor was the school merely expanding in size: its reputation was growing, too.

Having become one of the leading headmasters of his day, in 1865 Pears was invited to give evidence to the Schools’ Inquiry Commission; he also attended the first Headmasters’ Conference in 1869. He prized both academic excellence and sporting prowess and instigated schemes whereby fee-paying students subsidised scholars – this ensured that not only were there places at the school for the less privileged in society, but also that the school was able to attract the very best, whatever their background.

This then was the atmosphere in which the young Jeremy found himself and, it must be said, it was not an entirely happy match. Jeremy was not academic, nor was he particularly concerned about endearing himself to the masters. Even back then he was showing signs of the truculence that was to become his hallmark, something his headmaster recalled only too well. ‘It was like being prodded in the chest every day for five years,’ he (wearily) said.

Clarkson himself looks back on his schooldays with decidedly mixed views. ‘I think I must have been a spoilt brat at home because it was such a shock when I got to school to find that I wasn’t king of the hill anymore,’ he said, years later. ‘I was just another thirteen-year-old fag who was expected to sweep the corridors. And that’s why I took this conscious effort to be Jack the Lad, to drink and smoke, so that I could stand out. It was the best decision of my life. Smoking is just fantastic – I love it.’

His attitude towards his schooldays tended to change with his mood, though. On another occasion, he sounded considerably more enthusiastic. ‘Looking back, though, those were some of the best days of my life,’ he once remarked. ‘Boarding school was wonderful and I fitted in perfectly. My only disappointment is that no one ever tried to bugger me. I feel that’s a whole important part of growing up that I missed out on.’

But it was certainly different from home. Jeremy realised h

e had been spoilt in other ways too, not least by the quality of his father’s home cooking. ‘Steve was the cook,’ he recalled of his school days. ‘He is now cooking either at a prison or on the QE2. I was spoilt by father’s cooking, though even if I had been brought up in a Little Chef I would have been disappointed with Repton food. Grease. Water. Chicken: bone, air, skin. They should have been set free. Meat-free birds.’

Food was not his greatest concern back then, however. On another occasion, he recalled what had really occupied his time. ‘I was far more interested in the girls than lessons,’ he said. ‘My parents were in utter despair.’ He was developing into the personality he is now but, of course, what works well for a television presenter who won’t kowtow to anyone is not good in a truculent schoolboy. It was a difficult situation for all concerned.

Holidays, at least, were a relief. Clarkson was a typical lad about town, hanging out with his mates and chatting up girls and, very many years later, he recalled his attire du choix. It was what he later became famous for wearing, too. ‘Choosing the right jeans was critical,’ he said. ‘One wrong move and all the girls would openly laugh at you in the street. The flare had to come down exactly a quarter of an inch over your platform sole, and then, after I was introduced to The Clash, there had to be no flare at all – just a hole in the knee.

‘And under no circumstances could the jean be worn if a crease had been ironed into the front. This would leave an indelible mark: the mark of a man who lives at home with his mummy.’

These preoccupations were not to stay with him for long. Famously careless about his appearance as an adult, this is possibly the only period in his life when Jeremy was seriously concerned about clothes.

Of course, he was also having his formative experiences with girls. Clarkson was never exactly a ladies’ man per se, but right from the start he had a healthy interest in the opposite sex and he had quite a number of girlfriends before he finally settled down. Once asked if he’d ever been hurt, he replied, ‘Oh, by girlfriends occasionally. Everyone’s love life as a teenager is a terrible mess.’

Clarkson--Look Who's Back

Clarkson--Look Who's Back